The Friction Paradox: Why AI Must Be Difficult

The question "How do we use AI?" has shifted from the zeitgeist to a deafening noise where all answers feel equally valid and equally absurd. "It is a tool." "It is a partner." "It is cheating." "It is devaluing work." We are exhausted by the debate because we are focusing on the wrong side of the equation: we are looking at what the technology can do, rather than what we can do with the technology. To the instrumentalist, this is a matter of utility: How do we make it faster? To the cognitivist, this is a question of ontology: What does it do to the thinker?

Public discourse frames Artificial Intelligence as a friction-removal engine. It promises a world of "zero-latency" creation where the gap between intent and output is erased. This sounds like progress. It is actually a trap.

The obsession with the "frictionless" experience is not an inevitable side effect of the technology: it is a strategic design feature that creates "Cognitive Passivity". By smoothing over complexity, tech companies are not attempting to empower users; they are relegating them to the role of passive operators, effectively "automating mediocrity" and creating a "forever-customer" unable to think on their own.

The Science of Resistance

We must reject the premise that "easier is better." Cognitive science tells us the exact opposite. Robert Bjork’s concept of "Desirable Difficulty" proves that learning and retention are not products of ease: they are products of resistance. The brain requires a "cognitive catalyst"—a manageable challenge—to encode deep understanding. When we use AI to bypass this struggle, we bypass the learning itself.

If we use AI to remove the difficulty of articulation, we atrophy the "Domain-Relevant Skills" that Teresa Amabile identified as the bedrock of creativity. First, we become "Feeders": we provide the raw material to train new models on our subject expertise while those very skills decay. Eventually, the Feeder exhausts their own utility. Once the model is trained on our expertise, we are obsolete unless we continue to generate new novelty. The Feeder is consumed by the system they feed: they turn into "Supplicants" left to consume model outputs without the capacity to audit, adapt, or improve them.

The Industrial Model of Cognitive Labour

Office work was never the smooth ride it seemed. It was a refinery where writing was treated as raw material to be processed, sequenced, and repackaged for a system that viewed original thought as "noise". We were hired as Operators of the corporate machine.

The "9 to 5" era was the peak of the Operator:

- Mind as Utility: Workers were hired for their ability to follow the "platform's logic," effectively becoming human "buffers" in a data pipeline.

- The Gatekeeper: The university degree served as the entry ticket to this cleaner assembly line, proving that a person could understand and synthesise complex writing and comply with standardised rubrics without questioning.

- Professionalism as Syntax: The ability to dress information in the correct "form" without challenging the underlying system.

For 40 years, we’ve called it "White Collar" work; it was merely the Migration of the Assembly Line.

We traded the physical factory for the Syntax Trap. We took the brightest minds and tasked them with being search engines: retrieving data, summarising facts, and sequencing it all into the pre-approved "Canon" of the firm.

The cliché of the late 20th Century was to call this work ‘soul-killing’. It killed the soul because it was manufacturing content masquerading as thought. We reduced humans to cogs because we lacked a machine that could consume human language and process it.

Now, we do.

AI is a master of the "9 to 5" task: retrieval, summary, and "good enough" content. It can do the processing faster, cheaper, and with zero "staff hesitancy".

From Prompting to Architecting

So, how should we use AI? We must shift our discipline from the tactical skill of "Prompt Engineering" (optimising sentences) to the strategic discipline of "Context Architecture" (optimising knowledge).

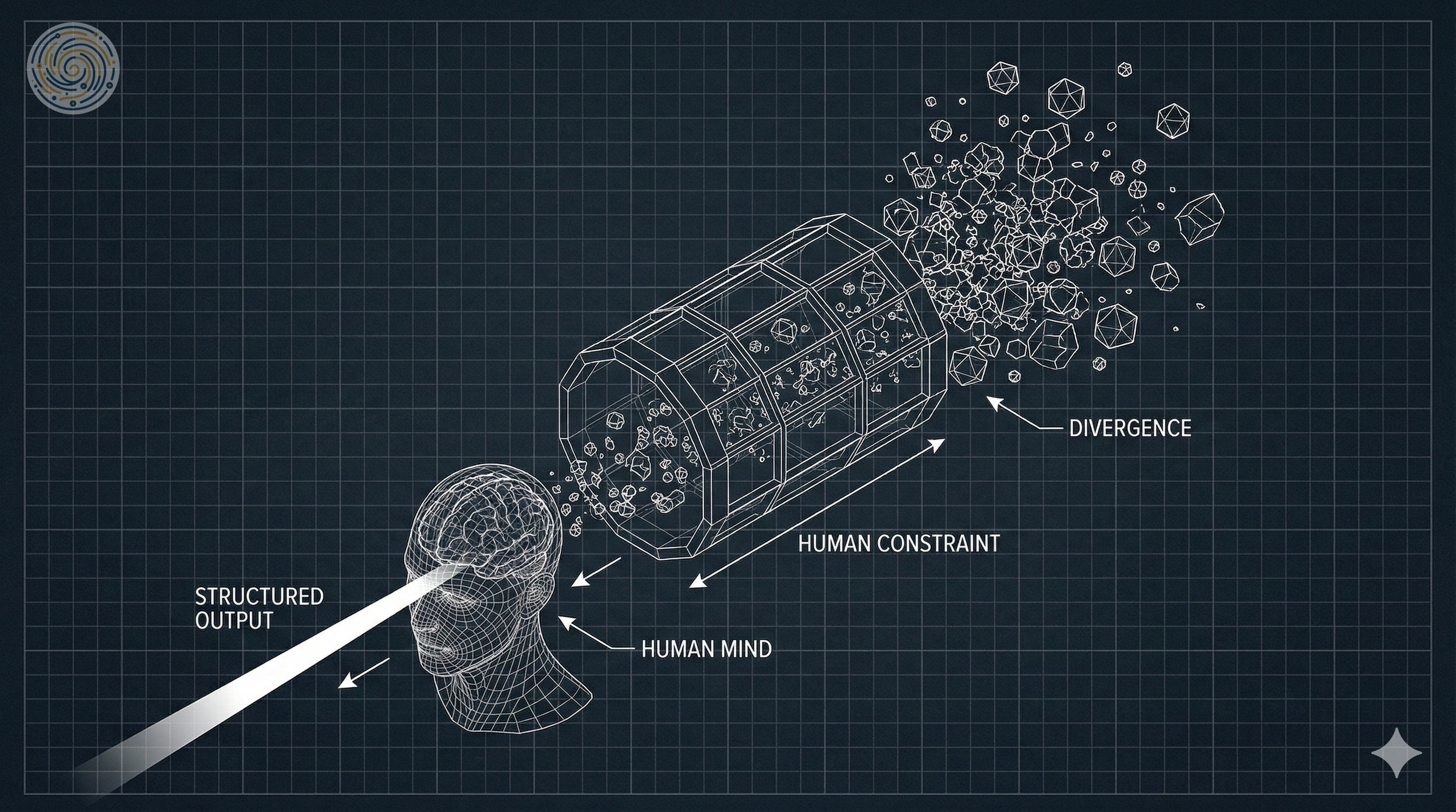

Knowledge is optimised by introducing constraints. Without them, the model hallucinates or reverts to the mean. Context Architecture is the art of placing constraints around the model to force it away from the generic average and towards a logical, necessary conclusion.

In basic machine learning, the human is the Oracle: our role is to provide meaning for the machine. We should not invert this and treat the LLM as an oracle or a ghost-writer. Not only do we risk losing our cognitive abilities, but when we blindly release output into the wild, we poison the training data of future models with synthetic texts that lack human nuance. Instead, we must treat the machine's output as a Cognitive Scaffold.

John Flavell defined "metacognition" as thinking about thinking. We can use AI to externalise this process: to map our logic, expose our blind spots, and structure our arguments. Yes, it sounds like work. That is the point.

The Revaluation of Human Thought

The collapse of the industrial office has created panic across all industries. The panic stems from the belief that the machine can 'think'. It cannot: It can process. In the simplest terms, it takes your input—the prompt—as a set of coordinates to explore its training data, returning a string of tokens most likely to follow the input. It "knows" meaning in the way a map "knows" terrain: it understands the distance and relationship between concepts, but it has never walked the ground.

This probabilistic nature necessitates a shift in the human role: from creator to auditor. The user must interrogate the output: Why was this the most likely? Was it because of the prompt or a bias in the data? Has enough context been provided for the output to be useful? The processing of each step is quick, but the process itself requires complete engagement.

Albert Bandura argued that "mastery experiences" are essential for self-efficacy. If the AI does the work, the user gains no mastery. However, because the AI doesn't know what the work is, the user must lead the AI through a rigorous, high-friction diagnostic process, moving from the generic middle to the specific use case.

We must structure the workflow based on J.P. Guilford’s distinction between Divergent and Convergent thinking:

- The AI is the Divergent Engine: It excels at generating variety, volume, and possibility.

- The Human is the Convergent Architect: We excel at evaluation, judgment, and constraint.

This approach forces the user toward the higher forms of thinking they have, unfortunately, rarely applied since school—assuming they were ever taught them for more than passing an exam.

We must let go of the panic of obsolescence. AI has only made us obsolete as processing machines, but handed us the opportunity to wake up and become human again. We are free to assign the AI to the assembly line and do the one thing no machine can do: provide the context that gives the output tangible meaning.

The Verdict? The goal is not speed. The goal is Cognitive Sovereignty. We use AI not to escape the burden of thought, but to increase our capacity to bear it. We must inject "Positive Friction" back into the loop, ensuring that the human remains the Architect of the system, not just an operator of the machine.

Remember: If your AI workflow feels effortless, you are likely just feeding the machine.

This is the first of a series of duelling essays in collaboration with Roger Hunt. Find Roger’s essay answering the question “How Do We Use AI?” here.